Getting GitOps Done

This post is intended as a bit of an overview of some of the topics we’ll cover and should cover GitOps as a concept. Throughout my career so far, there’s been a significant and noticeable change in engineering practice, that engineers are becoming more empowered to work across a broader set of tooling and take on more accountability and responsibility for broader engineering practices that may once have been split across many teams. As per Alexis Richardson’s definition of GitOps (CEO of Weaveworks and TOC for CNCF) - “Git as a system of record for the true state of your system or the true desired state, the one that you want it to be in”. I maintain it’s still largely a loose definition open to interpretation, in that to be truly effective in terms of low friction for engineers, it must go beyond that, this article will outline what I believe is an effective definition and how I’ve seen it implemented.

What is GitOps?

While it’s quite difficult to pin down whether it’s a framework, a methodology, a mindset a belief system or, a pattern. My thoughts on it are that all dependencies of the build/deploy/run software development lifecycle should be defined as code, automated, and left free of pesky human interaction other than when writing code.

How is this different from CI/CD?

You may find yourself asking why we might use this approach, simply put, a well-implemented GitOps strategy can significantly increase productivity for a cross-functional team by reducing friction and dependency on manual input for deployments, architecture, and infrastructure changes. Additionally, you get the benefit of viewing the git history to revert to the last known good state, although this comes with its own benefits and drawbacks.

GitOps is an evolution of Infrastructure as Code (IaC), Everything as Code, ideally we’d want to store everything: architecture designs, documentation, codebase, infrastructure, configuration, tests, glue, and anything else that’s required to run your system, as code in some form. While this diagram has been around seemingly since the dawn of time, it does highlight that usually there’s quite a bit involved in getting code out to production in a timely, reliable, and secure manner (YMMV).

For this to work in practical terms, you need to subscribe to the following key tenets. Your project must:

Use git as the single source of truth

Treating your git repository as the golden record, you could liken it to the mutable vs immutable infrastructure debate (here’s a nice gruntwork article on it). Your code should define what your platform should look like as opposed to its current state, if it fails as part of the provisioning, you need to ensure you have the appropriate measures in place to rectify it. Through the use of continuous delivery tooling, we’d look at regularly applying changes across environments uniformly and incrementally to ensure there’s no drift between the code (i.e. the head of the main branch) and the configuration.

Define all dependencies as code

As an engineer, you’re comfortable defining and releasing functional changes to a codebase, understanding the impact of a breaking code-change is part of planning any sort of release. When applying this to GitOps, you’re applying it also to the broader codebase including the deployment platform, your container definition, your configuration as well as connectivity.

Bringing it all together

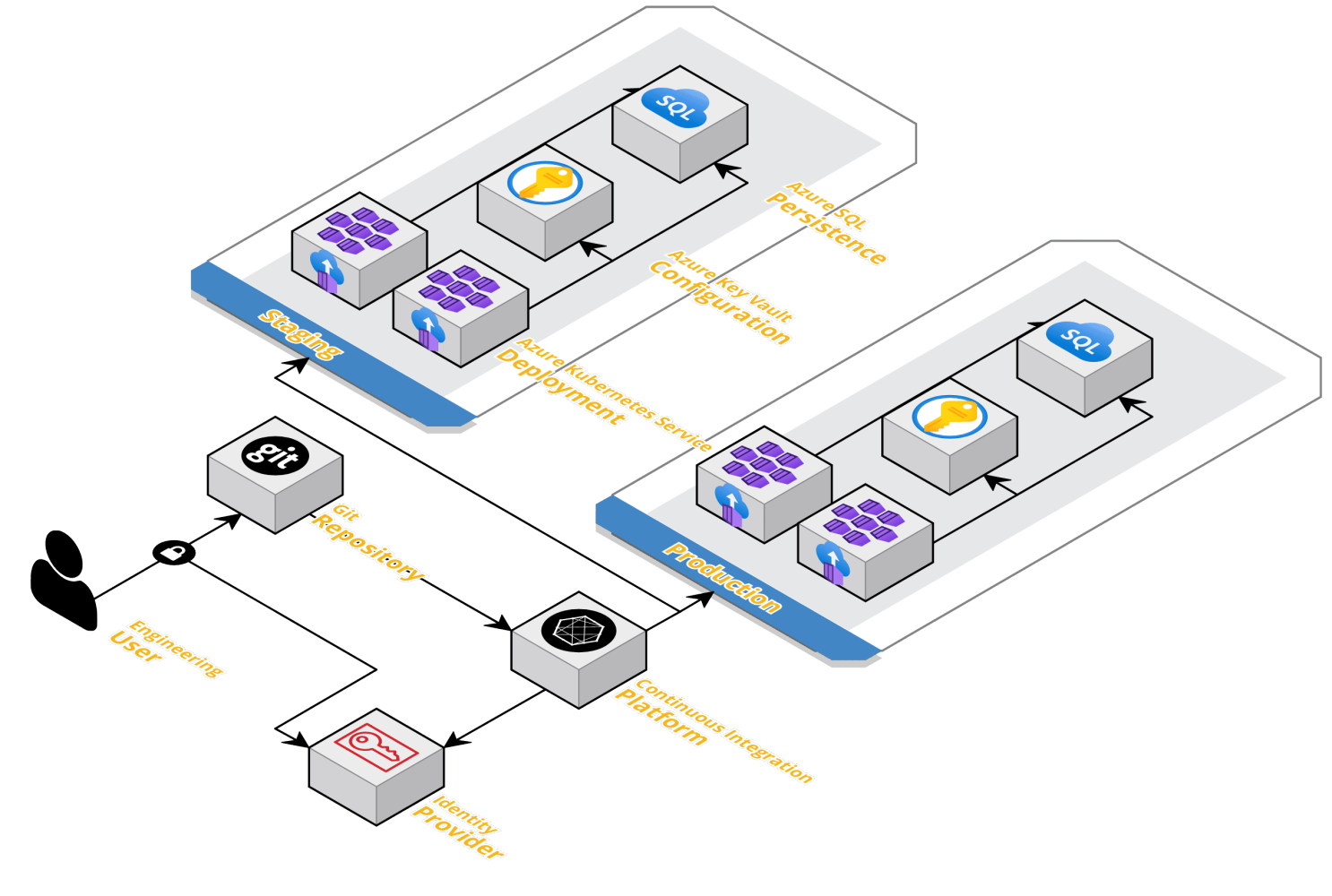

We’ve spoken at length now around what GitOps means and how, at a high level we’re able to realise some of the benefits, but really without an effective Continuous Integration and Continuous Deployment (CICD) platform configured, many of the benefits of GitOps are not realisable, we’ll look to cover some of the common patterns and designs here. This diagram outlines at a high level, some common components in any modern CICD configuration which has been largely unchanged from “traditional” patterns, we’ll look at the following architecture as the basis of this series of blogs.

I’ve aimed to keep the tooling as “swappable” as possible from a GitOps perspective, but have chosen to provision some of the items above in Azure. We may end up swapping up some of the Azure provided items for open-source equivalents, but we’ll see how we get on as this blog progresses. In this blog, we’ll be looking at provisioning an ensemble of microservices, that are fully automated, zero-touch, and with appropriate testing to ensure that we’re comfortable releasing into “production”.

Benefits

This might sound like we’d need to do a lot in terms of integrations and sticking rigidly to this hands-off approach, so what are the benefits? Subscribing to the GitOps pattern facilitates engineering quality, security through simplification, but often requires a significant amount of upfront effort in terms of building and integrating the various tools required to facilitate this approach.

Security

Approaching the management of our repositories in this way enables us to build tooling to allow engineers escalated privileges in a controlled and managed way without having to delegate roles and access in production environments etc. A practical example of this would be sealed secrets. In which you would use a known encryption key to “seal” a secret, and commit the encrypted value to git, this concept will be explored further in this series of blog posts.

Observability

When we make a change to the codebase, we’re able to see the downstream impact thereof. Given a good GitOps setup will include downstream pipelines to run tests and deployments, we’ll be able to see the impact of a change across environments ahead of time. Again, this is a concept that will be explored further in this series of posts.

Autonomy

Given that the goal of any Developer Experience team is to facilitate the path-to-production for teams to be able to deploy with low friction, the fundamental enabler of this would be to remove critical dependencies on team members; provided teams have adequate tooling and documentation. In addition to this, it provides significant benefits in that given everything is automated, the code should be descriptive enough to act as its own documentation, providing engineers with repeatable deployments and configuration management.

Challenges

No alt text provided for this image It’s easy to extoll the virtues of a shiny methodology or approach without practicing it effectively or analysing shortcomings of the approach. Ultimately, we should look to GitOps as a means of moving towards a more “DevOps” culture, in that self-organising, autonomous highly effective teams that deliver value to end customers.

Tooling Churn

A drawback I personally find is more of a general complaint about cloud-native engineering than it is with GitOps specifically, but there is a high degree of tooling churn in this space. I find it easy to get lost in the latest shiny new framework or tool that

Organisation

For me, the biggest challenge of this approach is more organisational, the often huge shift in responsibility and accountability for engineers. Fundamentally, we’re asking engineers to own code from dev through to production. This fosters a more collaborative environment to work in as all engineers are working on the same codebase; it can be a significant organisational challenge to ensure the same level of rigor and quality goes into each PR whilst having the appropriate level of oversight.

The biggest impact for a delivery team would be that it’s likely to reduce individual project cadence, but increase overall delivery cadence when adopted and matured as an approach broadly. Given traditional waterfall projects will have dedicated infrastructure, service, and testing phases, squashing this all into one collaborative effort is often difficult to manage and still ends up with specialisms in various areas

Maturity

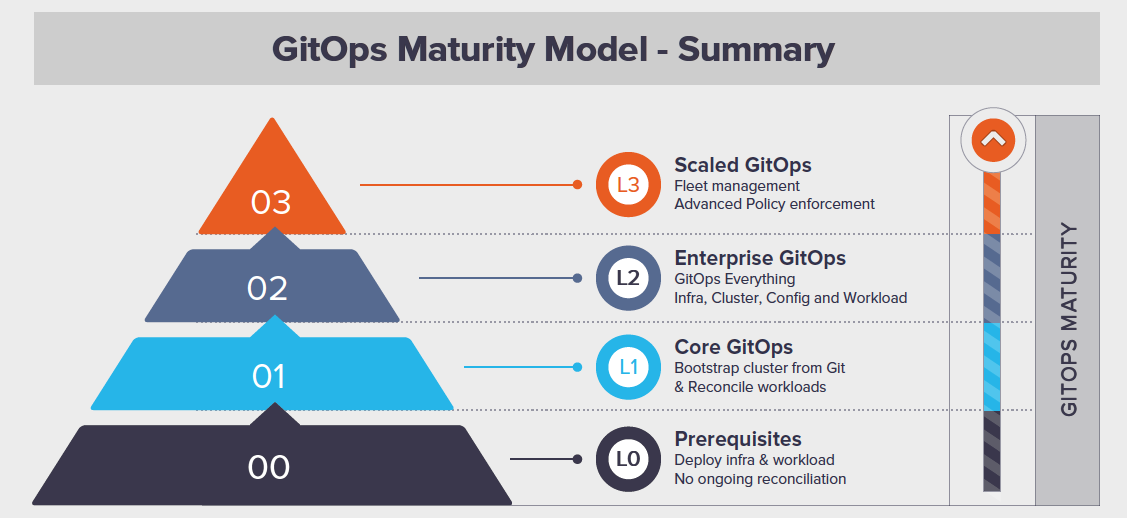

In many IT frameworks, tools, patterns, we get a set of maturity measures, and GitOps is no exception, aside from the (usually pretty vague and management-y) DevOps maturity model diagrams that are banded around, the Weaveworks GitOps maturity model is pretty specific in terms of measuring the approach.

Whilst we will get a lot of benefits from progressing up this pyramid, it is no small task to do so. I find that to do so requires dedicated resource to work exclusively on maturing the tooling approach to allow engineers to begin adoption of this framework. Personally, I’m a big advocate of the “you must be this tall to ride” approach in terms of staggering incremental changes to roadmaps and empowering engineering teams to strive to change behaviours to be able to realise the benefits provided.

GitOps as a solution to all your problems

There are no silver bullets! In the same way that “doing” Agile or DevOps don’t automatically fix all your software engineering and organisational problems, “doing” GitOps doesn’t solve your platform-related issues. You still need to ensure the appropriate checks and balances are in place and continuously evolve your approach your needs evolve. Given we’ll likely be adopting GitOps in organisations under the banner of “DevOps”, the built-in assumption is that this is not the end state. It assumes that your tooling will keep moving forward and things will change, the previous new way will soon become obsolete, so as much as ever in engineering, I think it’s important to be as agnostic as possible when it comes to tooling choices and interface designs. Additionally, need to ensure that the “you must be this tall to ride” is not a barrier-to-entry and instead look to ensure that the framework and tooling provided are accessible, easily understood, and self-documenting where possible.

Summary

GitOps aims to get to a model in which a set of dependencies are defined in a git repository as code, and there’s effective automation that ensures the deployment target accurately reflects the state of the repository and fulfills required non-functional requirements such as testing, security, monitoring and so on.

1

code in repo == deployed to environment

This series of blog posts will aim to cover the key principles, approaches, and tools used when implementing GitOps in practice.